This blog is a preview of our 2022 Crypto Crime Report. Sign up here to download your copy now!

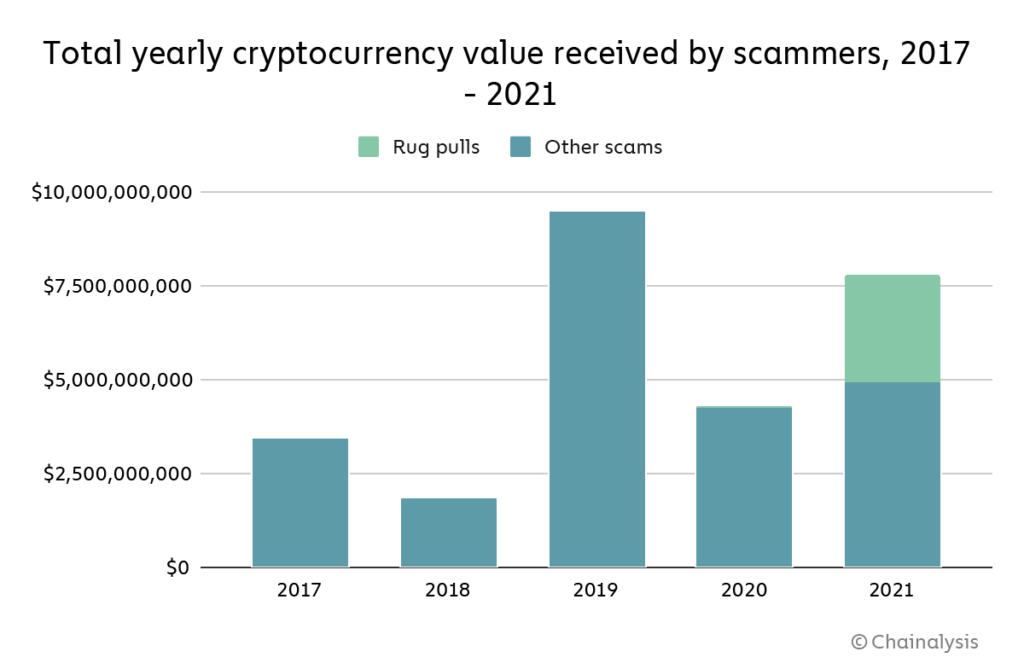

Scams were once again the largest form of cryptocurrency-based crime by transaction volume, with over $7.7 billion worth of cryptocurrency taken from victims worldwide.

That represents a rise of 81% compared to 2020, a year in which scamming activity dropped significantly compared to 2019, in large part due to the absence of any large-scale Ponzi schemes. That changed in 2021 with Finiko, a Ponzi scheme primarily targeting Russian speakers throughout Eastern Europe, netting more than $1.1 billion from victims.

Another change that contributed to 2021’s increase in crypto scam revenue: the emergence of rug pulls, a relatively new scam type particularly common in DeFi, in which the developers of a cryptocurrency project — typically a new coin — abandon it unexpectedly, taking users’ funds with them. We’ll look at both rug pulls and the Finiko Ponzi scheme in more detail later in the report.

As the largest form of cryptocurrency-based crime and one uniquely targeted toward new users, crypto scams pose one of the biggest threats to cryptocurrency’s continued adoption. But as we’ll explore, some cryptocurrency businesses are taking innovative steps to leverage blockchain data to protect their users and nip scams in the bud before potential victims make deposits.

Cryptocurrency investment scams in 2021: More scams, shorter lifespans

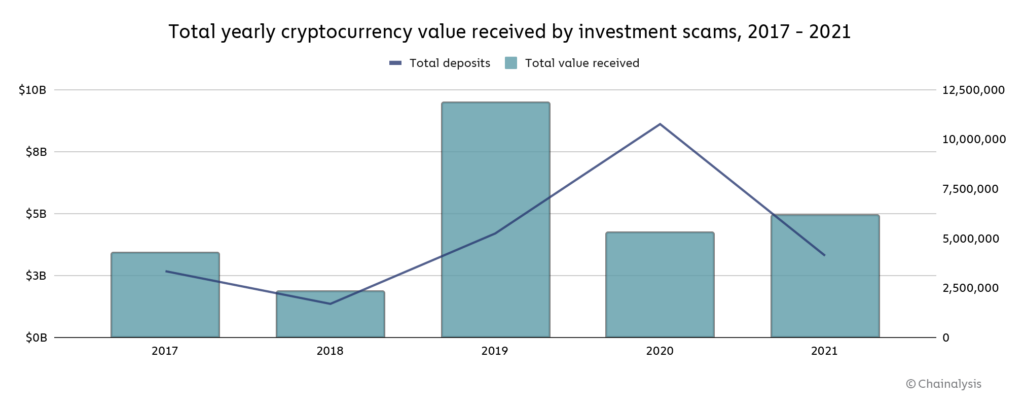

While total crypto scam revenue increased significantly in 2021, it stayed flat if we remove rug pulls and limit our analysis to investment scams — even with the emergence of Finiko. At the same time though, the number of deposits to scam addresses fell from just under 10.7 million to 4.1 million, which we can assume means there were fewer individual scam victims.

This also tells us that the average amount taken from each victim increased.

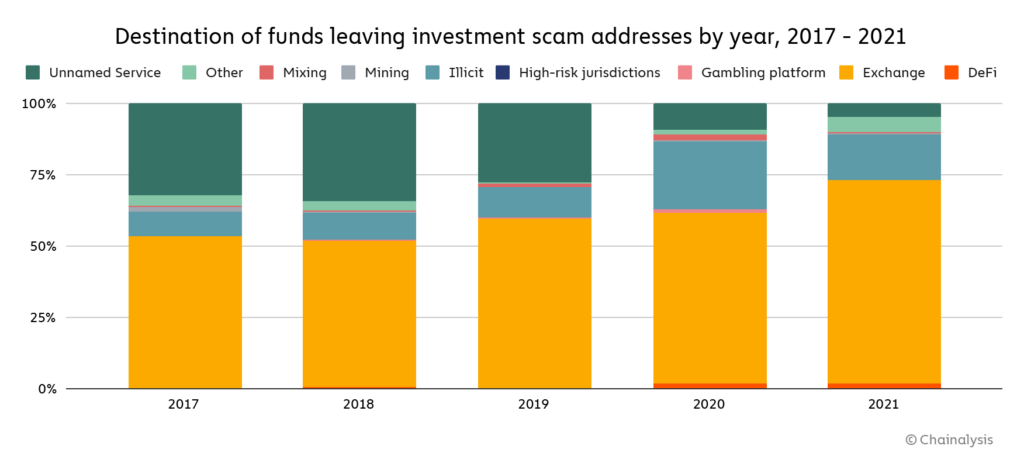

Scammers’ money laundering strategies, however, haven’t changed all that much. As was the case in previous years, most cryptocurrency sent from scam addresses ended up at mainstream exchanges.

Cryptocurrency exchanges using Chainalysis KYT for transaction monitoring can see this activity in real time, and take action to prevent scammers from cashing out.

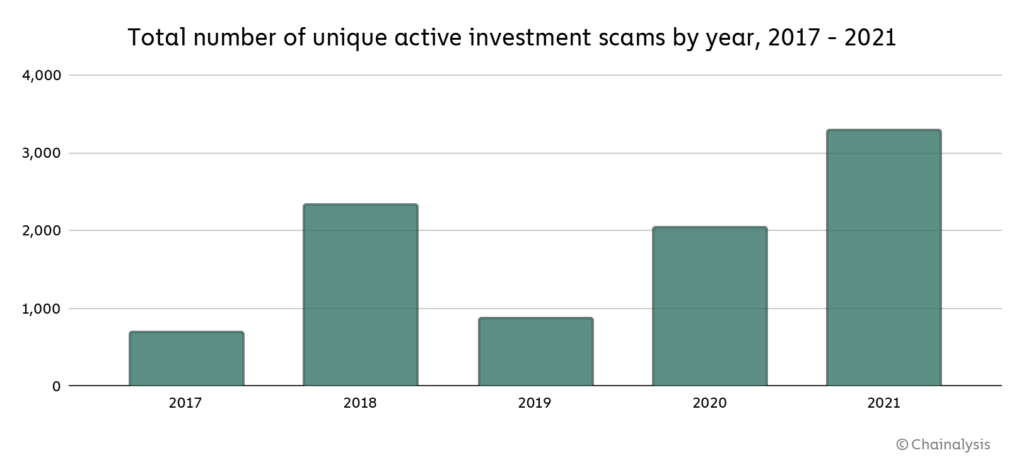

The number of financial scams active at any point in the year — active meaning their addresses were receiving funds — also rose significantly in 2021, from 2,052 in 2020 to 3,300.

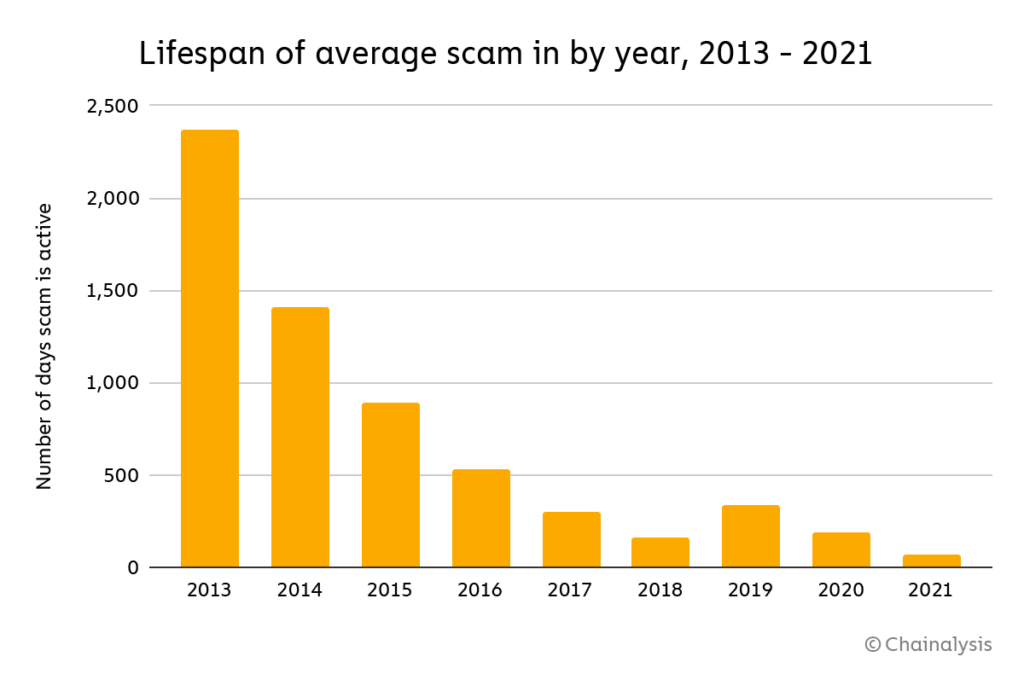

This goes hand in hand with another trend we’ve observed over the last few years: The average lifespan of a financial scam is getting shorter and shorter.

The average financial scam was active for just 70 days in 2021, down from 192 in 2020. Looking back further, the average cryptocurrency scam was active for 2,369 days, and the figure has trended steadily downwards since then. One reason for this could be that investigators are getting better at investigating and prosecuting scams. For instance, in September 2021, the CFTC filed charges against 14 investment scams touting themselves as providing compliant cryptocurrency derivative trading services — a common scam typology in the space — whereas in reality they had failed to register with the CFTC as futures commission merchants. Previously, these scams may have been able to continue operating for longer. As scammers become aware of these actions, they may feel more pressure to close up shop before drawing the attention of regulators and law enforcement.

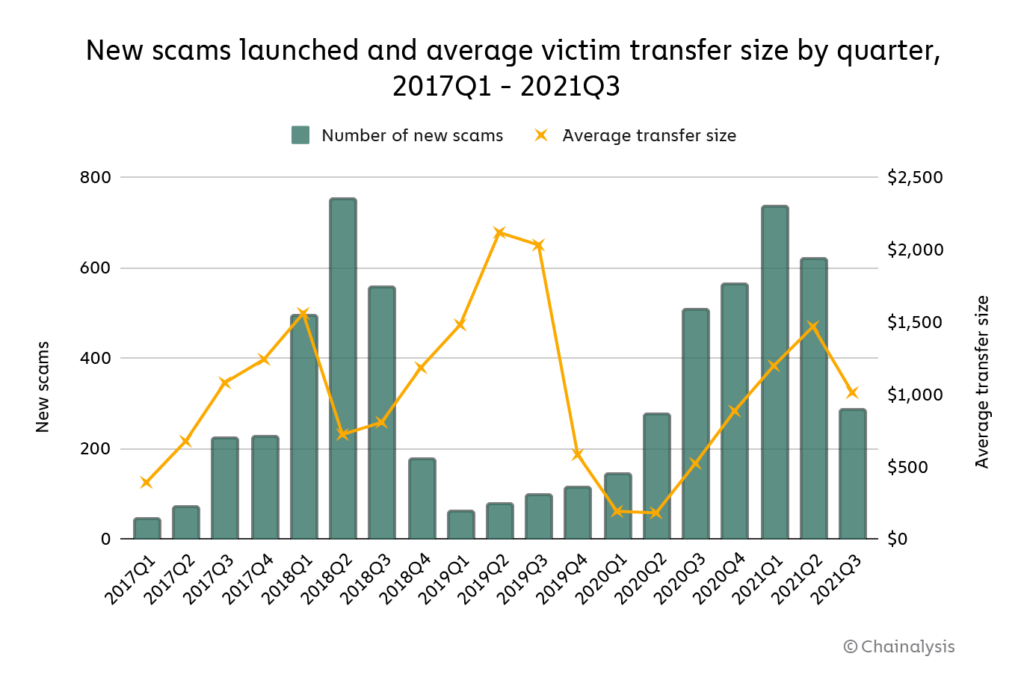

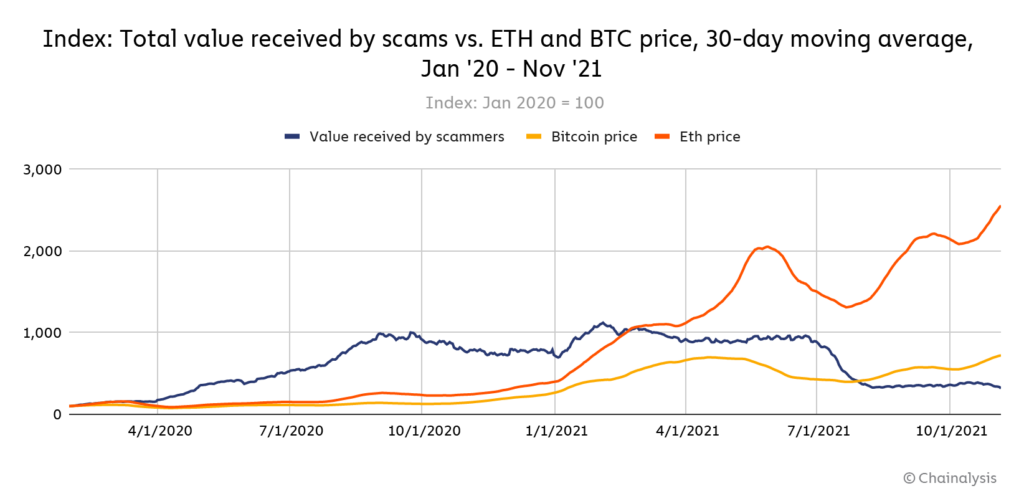

At the same time, we’re seeing the end of a long-standing statistical relationship between cryptocurrency asset prices and scamming activity. Scams typically come in waves corresponding with sustained price growth in popular cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, which typically also lead to influxes of new users. We see this reflected in the chart below — scamming activity spiked following bull runs in 2017 and 2020.

This isn’t all that surprising. New, less savvy users attracted by cryptocurrency’s growth are more likely to fall for scams than more seasoned users. However, the relationship between asset prices and scamming activity now appears to be disappearing.

Above, we see scam activity rise in concert with Bitcoin and Ethereum prices until 2021, when scamming activity stays flat and even begins to drop regardless of whether prices rise or fall.

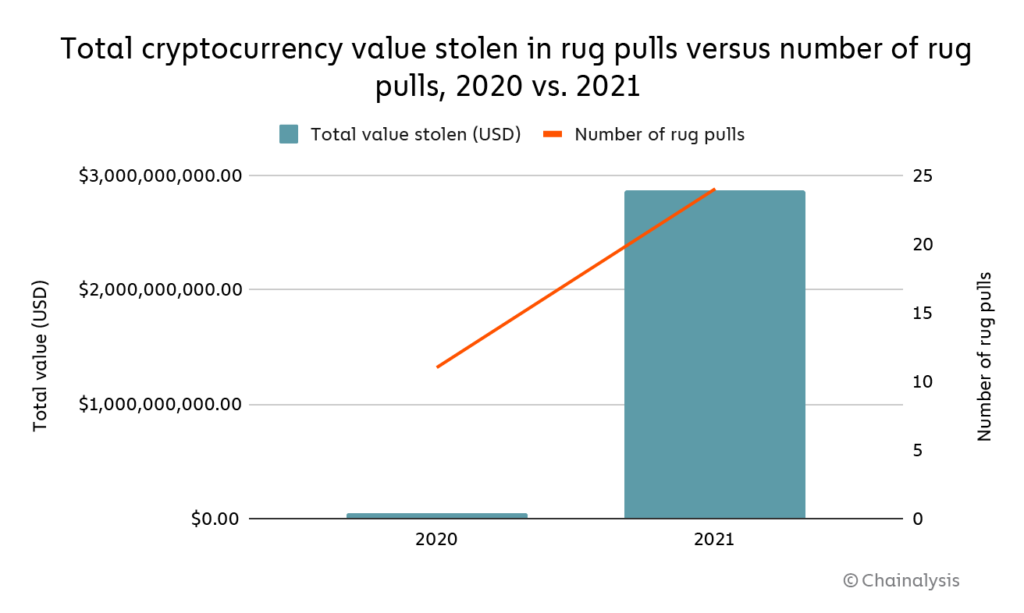

Rug pulls are the latest innovation in scamming

Rug pulls have emerged as the go-to scam of the DeFi ecosystem, accounting for 37% of all cryptocurrency scam revenue in 2021, versus just 1% in 2020.

All in all, rug pulls took in more than $2.8 billion worth of cryptocurrency from victims in 2021.

As is the case with much of the emerging terminology in cryptocurrency, the definition of “rug pull” isn’t set in stone, but we generally use it to refer to cases in which developers build out what appear to be legitimate cryptocurrency projects — meaning they do more than simply set up wallets to receive cryptocurrency for, say, fraudulent investing opportunities — before taking investors’ money and disappearing.

Rug pulls are most commonly seen in DeFi. In a rug pull, a scammer creates a new token and then promotes it to crypto investors on the basis of false promises, who buy the new token in the hopes that it will rise in value,. This provides liquidity to the project, and is how most DeFi projects — not just scams — start out. In rug pulls, however, the developers drain the funds from the liquidity pool, sending the token’s value to zero, and disappear.

Rug pulls are prevalent in DeFi because with the right technical know-how, it’s cheap and easy to create new tokens on the Ethereum blockchain or others and get them listed on decentralized exchanges (DEXes) without a code audit. That last point is crucial — decentralized tokens are meant to be designed in such a way that investors holding governance tokens can vote on things like how assets in the liquidity pool are used, which would make it impossible for the developers to drain the pool’s funds. While code audits that would catch these vulnerabilities are common in the space, they’re not required in order to list on most DEXes, hence why we see so many rug pulls.

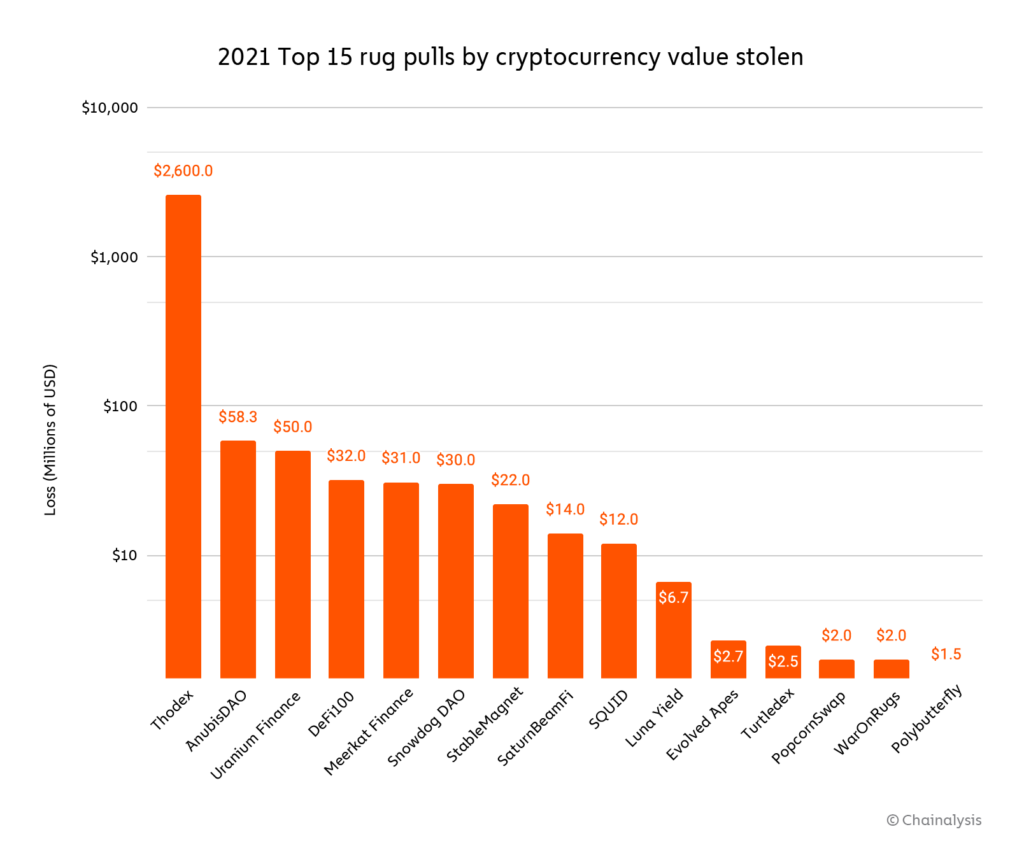

The chart below shows 2021’s top 15 rug pulls in order of value stolen.

It’s important to remember that not all rug pulls start as DeFi projects. In fact, the biggest rug pull of the year centered on Thodex, a large Turkish centralized exchange whose CEO disappeared soon after the exchange halted users’ ability to withdraw funds. In all, users lost over $2 billion worth of cryptocurrency, which represents nearly 90% of all value stolen in rug pulls. However, all the other rug pulls in 2021 began as DeFi projects.

AnubisDAO, the second-biggest rug pull of 2021 at over $58 million worth of cryptocurrency stolen, provides an excellent example of how rug pulls in DeFi work.

AnubisDAO’s Twitter banner. Credit CryptoHubK

AnubisDAO’s Twitter banner. Credit CryptoHubK

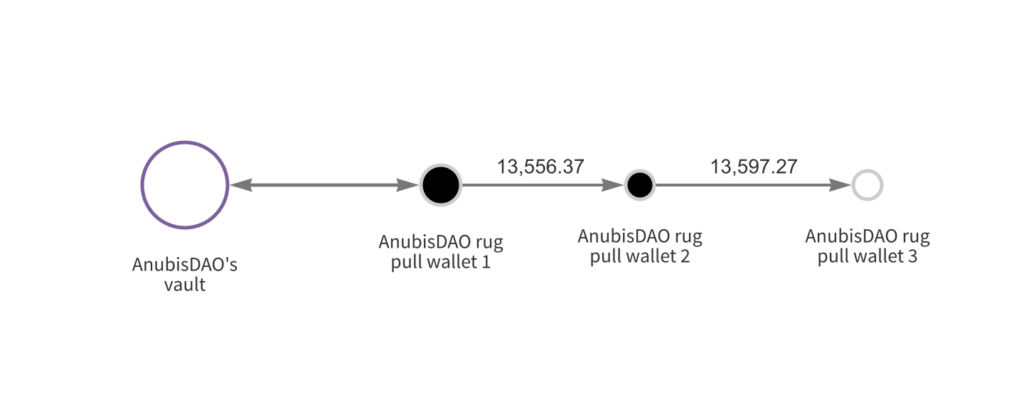

AnubisDAO launched on Thursday, October 28, 2021, claiming it planned to provide a decentralized, free-floating currency backed by a basket of assets. With little more than a DOGE-inspired logo — the project had no website or white paper, and all of its developers went by pseudonyms — AnubisDAO raised nearly $60 million from crypto investors practically overnight, all of whom received the project’s ANKH token in exchange for funding the project’s liquidity pool. But a mere 20 hours later, all the funds raised, primarily held in wrapped Ethereum (wETH), disappeared from AnubisDAO’s liquidity pool, moving to a series of new addresses.

We can see these transactions on the graph above. AnubisDAO used contracts created with the Balancer Liquidity Bootstrapping Protocol to receive and hold the wETH investors sent to their liquidity pool in exchange for ANKH tokens. However, the address that deployed the liquidity pool contract was already in possession of the vast majority of the liquidity provider (LP) tokens for that pool. 20 hours after the sale began, the address that created the pool cashed out it’s massive holdings of LP tokens, allowing them to make off with nearly all the wETH and ANKH tokens in the pool.

The thief then moved that wETH through a series of intermediary wallets. Soon after this, the Twitter account that had acted as the public face of AnubisDAO went offline, and ANKH’s value plummeted to zero.

Since the theft, there’s been a great deal of finger pointing and conflicting explanations. One of the project’s pseudonymous founding developers claims another founder, who had access to AnubisDAO’s liquidity pool, is solely responsible for the rug pull, while that founder claims to have fallen victim to a phishing attack that compromised the pool’s private keys — the evidence that founder has supplied doesn’t support that theory, however. At this time, all signs point to a standard rug pull, but it’s unclear whether or not all of the developers were in on it.

AnubisDAO should serve as a cautionary tale to investors evaluating similar opportunities. The most important takeaway is to avoid new tokens that haven’t undergone a code audit. Code audits are a process by which a third-party firm analyzes the code of the smart contract behind a new token or other DeFi project, and publicly confirms that the contract’s governance rules are iron clad and contain no mechanisms that would allow for the developers to make off with investors’ funds. They can also check for security vulnerabilities that could be exploited by hackers. OpenZeppelin is one example of a firm that provides code audits, but there are several others that are also considered trustworthy. Investors may also want to be wary of tokens that lack the public-facing materials one would expect from a legitimate project, such as a website or white paper, as well as tokens created by individuals not using their real names.

DeFi is one of the most exciting, innovative areas of the cryptocurrency ecosystem, and there are clearly big opportunities for early adopters. But the newness of the space and relative inexperience of many investors provides a prime landscape for scamming opportunities by bad actors. It’ll be difficult for DeFi’s growth to continue if potential new users don’t feel they can trust new projects, so it’s important that trusted information sources in cryptocurrency — whether they’re influencers, media outlets, or project participants — help new users understand how to spot shady projects to avoid.

Finiko: 2021’s billion dollar Ponzi scheme

Finiko was a Russia-based Ponzi scheme that operated from December 2019 until July 2021, at which point it collapsed after users found they could no longer withdraw funds from their accounts with the company. Finiko invited users to invest with either Bitcoin or Tether, promising monthly returns of up to 30%, and eventually launched its own coin that traded on several exchanges.

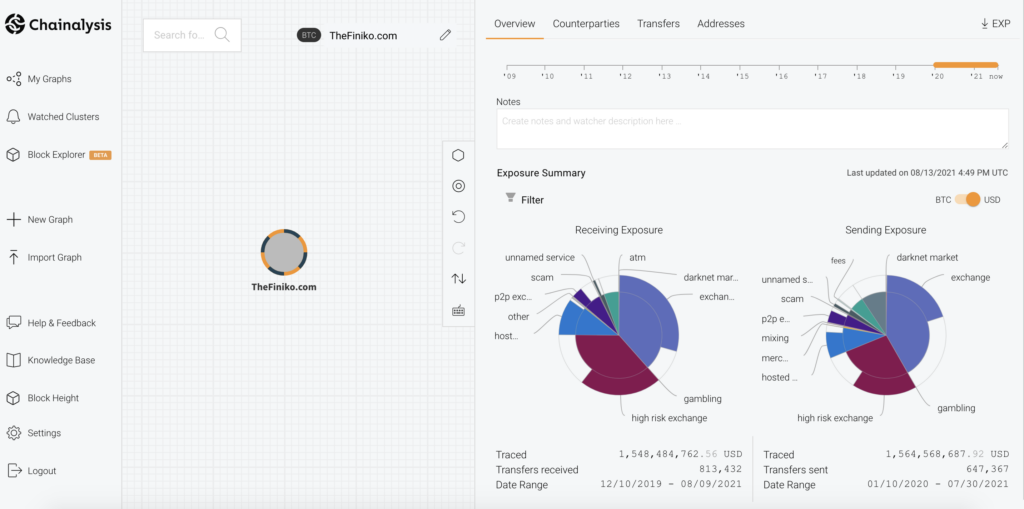

According to the Moscow Times, Finiko was headed up by Kirill Doronin, a popular Instagram influencer who has been associated with other Ponzi schemes. The article notes that Finiko was able to take advantage of difficult economic conditions in Russia exacerbated by the Covid pandemic, attracting users desperate to make extra money. Chainalysis Reactor shows us how prolific the scam was.

During the roughly 19 months it remained active, Finiko received over $1.5 billion worth of Bitcoin in over 800,000 separate deposits. While it’s unclear how many individual victims were responsible for those deposits or how much of that $1.5 billion was paid out to investors to keep the Ponzi scheme going, it’s clear that Finiko represents a massive Bitcoin fraud perpetrated against Eastern European cryptocurrency users, predominantly in Russia and Ukraine.

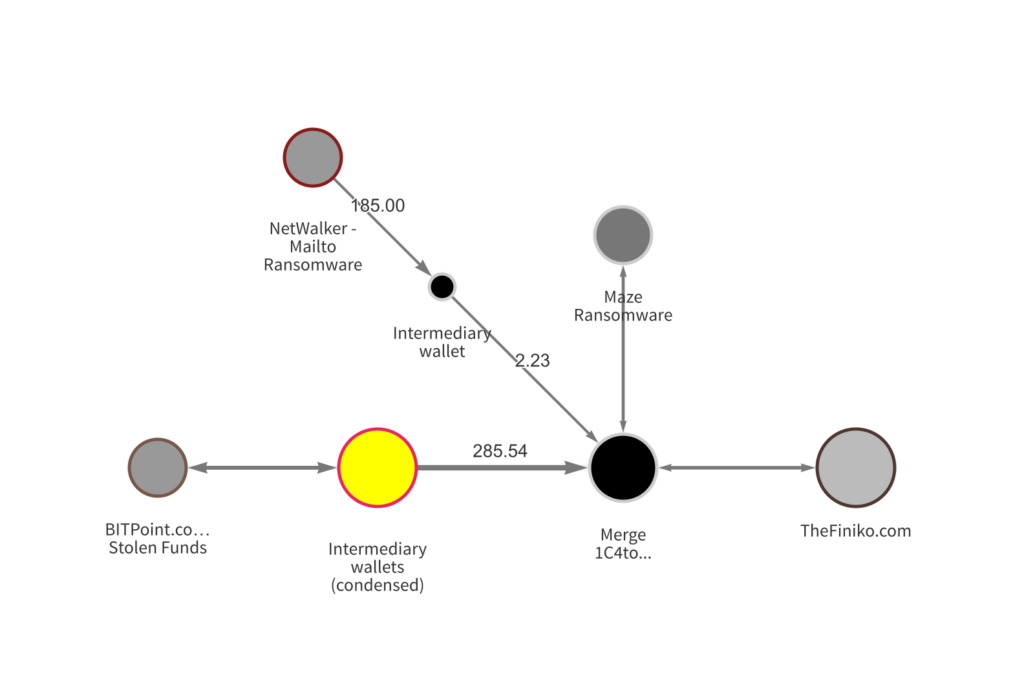

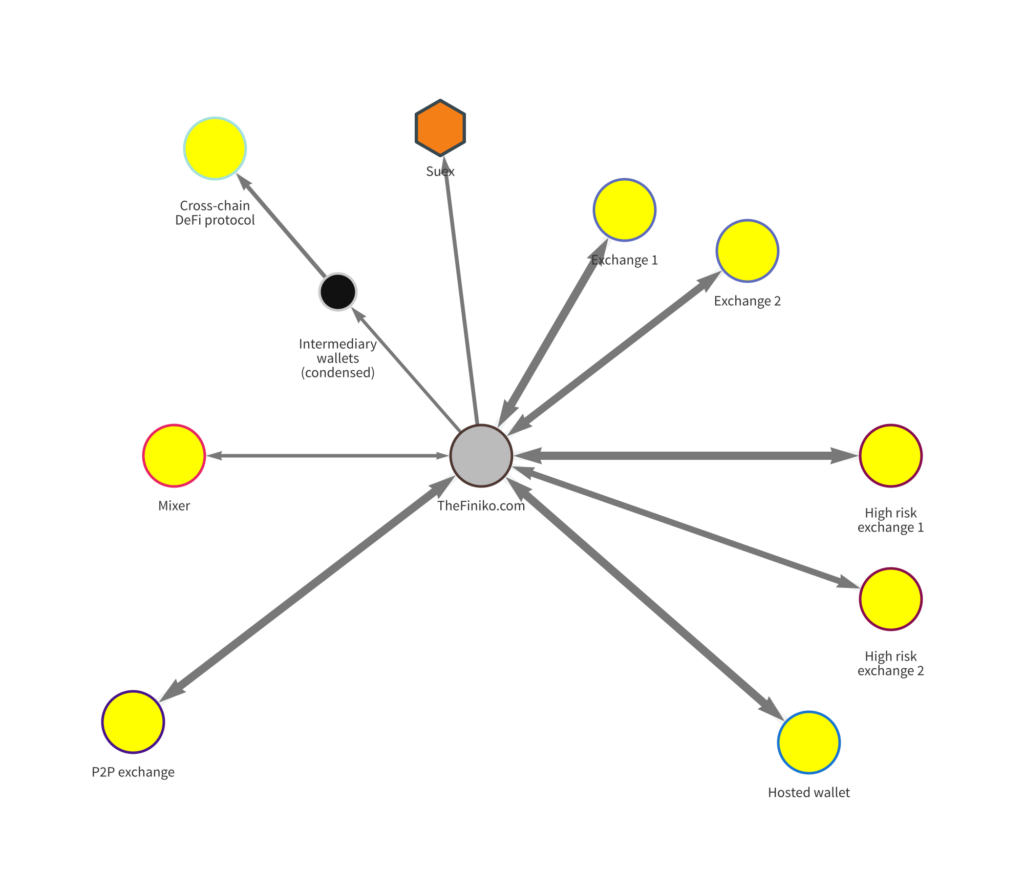

As is the case with most crypto scams, Finiko primarily received funds from victims’ addresses at mainstream exchanges. However, we can also see that Finiko received funds from what we’ve identified as a Russia-based money launderer.

This launderer has received millions of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency from addresses associated with ransomware, exchange hacks, and other forms of cryptocurrency-based crime. While the amount the service has sent to Finiko is quite small — under 1 BTC total — it serves as an example of how a scam can also be used to launder funds derived from other criminal schemes. It’s also possible that Finiko has received funds from other laundering services we’ve yet to identify.

Finiko sent most of its more than $1.5 billion worth of cryptocurrency to mainstream exchanges, high-risk exchanges, a hosted wallet service, and a P2P exchange. However, we don’t know what share of those transfers represent payments to victims in order to give the appearance of successful investments.

Finiko also sent $34 million to a DeFi protocol designed for cross-chain transactions via a series of intermediary wallets, where it was likely converted into ERC-20 tokens and sent elsewhere. It also sent roughly $3.9 million worth of cryptocurrency to a few popular mixing services.

Most interesting of all though is Finiko’s transaction history with Suex, an OTC broker that was sanctioned by OFAC for its role in laundering funds associated with scams, ransomware attacks, and other forms of cryptocurrency-based crime. Between March and July of 2020, Finiko sent over $9 million worth of Bitcoin to an address that now appears as an identifier on Suex’s entry into the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) List. This connection underlines the prolificness of Suex as a money laundering service, as well as the crucial role of such services generally in allowing large-scale cybercriminal operations like Finiko to victimize cryptocurrency users.

Soon after Finiko’s collapse in July 2021, Russian authorities arrested Doronin, and later also nabbed Ilgiz Shakirov, one of his key partners in running the Ponzi scheme. Both men remain in custody, and arrest warrants have reportedly been issued for the rest of Finiko’s founding team.

How one cryptocurrency platform is saving users from scams

Mainstream cryptocurrency platforms like exchanges are in the perfect position to fight back against scams and instill more trust in cryptocurrency by warning users or even preventing them from executing those transactions. One popular platform did just that in 2021, and the results were extremely promising.

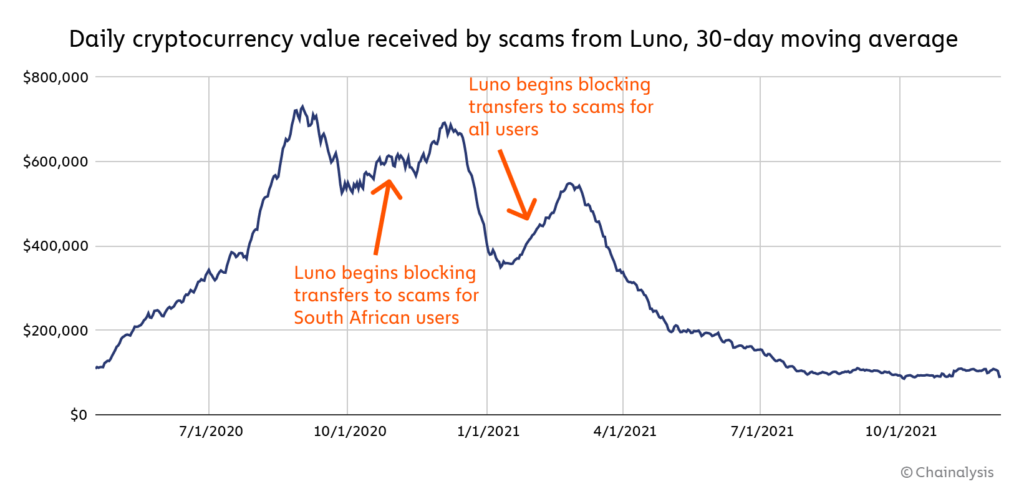

Luno is a leading cryptocurrency platform operating in over 40 countries, with an especially heavy presence in South Africa. In 2020, a major scam was targeting South African cryptocurrency users, promising outlandishly large investment returns. Knowing that its users were at risk, Luno decided to take action in partnership with Chainalysis.

The first step was a warning and education campaign. Using in-app messages, help center articles, emails, webinars, social media posts, YouTube videos, and even one-on-one conversations, Luno showed users how to spot the red flags that indicate an investment opportunity is likely a scam, and taught them to avoid pitches that appear too good to be true.

Luno then went a step further and began preventing users from sending funds to addresses it knew belonged to scammers. That’s where Chainalysis came in. As the leading blockchain data platform, we have an entire team dedicated to unearthing cryptocurrency scams and tagging their addresses in our compliance products. With that data, Luno was able to halt users’ transfers to scams before they were processed. It was a drastic strategy in many ways — cryptocurrency has historically been built on an ethos of financial freedom, and some users were likely to chafe at a perceived limitation on their ability to transact. But thanks to Chainalysis’ best in class cryptocurrency address attributions, Luno was able to establish the trust necessary to sell customers on the strategy.

Luno first began blocking scam payments for South African users only in November 2020, and then rolled the feature out worldwide in January 2021. The plan worked, and transfers from Luno wallets to scams fell drastically over the course of 2021.

The moving 30-day average daily transaction volume of transfers to scams fell 88% from $730,000 at its peak in September 2020, to just $90,000 by November. One customer summed up the results perfectly, saying, “Thank you, Luno. I was about to lose my pension and savings.”

Scams represent a huge barrier to successful cryptocurrency adoption, and fighting them can’t be left only to law enforcement and regulators. Cryptocurrency businesses, financial institutions, and, of course, Chainalysis have an important role to play as well. With this strategy, Luno took a courageous step towards establishing greater trust and safety in cryptocurrency, which we hope to continue to see grow in the industry.

This blog is a preview of our 2022 Crypto Crime Report. Sign up here to download your copy now!